Condition?

What Condition?

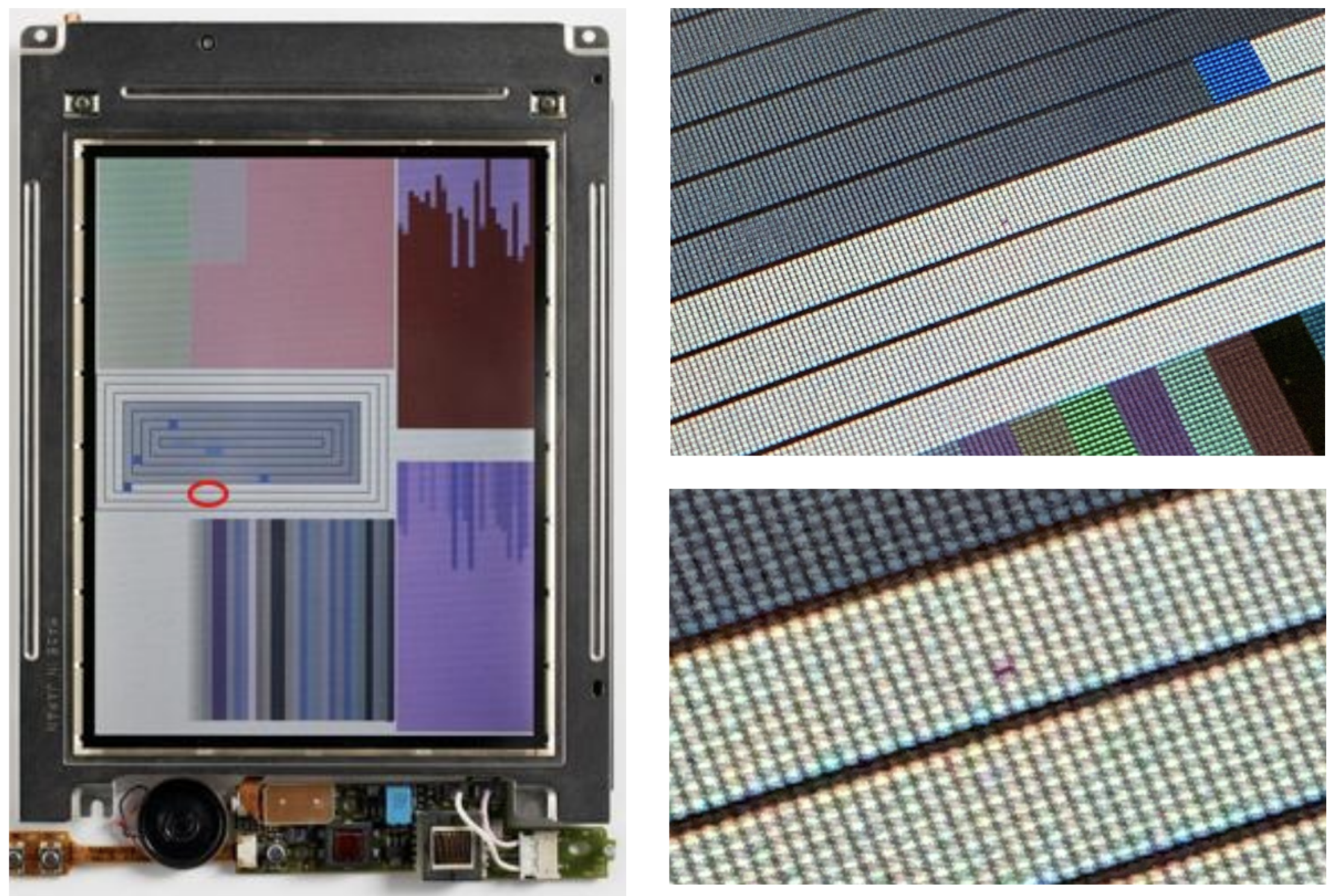

Some time-based media artworks need to be activated in order to be understood and cared for appropriately. Such is the case with John F. Simon, Jr.’s work from 1999 titled Color Panel v1.0. The work was acquired by The Brooklyn Museum over a decade ago and, during my 2021 summer placement in their time-based media and objects conservation labs, I was tasked with helping catalog the artwork and its components. The research and documentation-based conservation work I did there ultimately helped the museum build institutional knowledge about an important piece in their collect.

Assessing Condition

In most cases, simply approaching and looking at a work of art (a painting on a wall, for example) will give you a good general idea of its condition. This isn’t the case when it comes to many software-based artworks, where a blank screen may indicate the work is dead or just unplugged.

In time-based media artworks, it’s important to define which properties of the piece make up its core identity and which aspects are variable. In several interviews that I was able to find the artist has stated that the code and the hardware are not variable and should be maintained as well as possible. In fact, he said that the piece should only be displayed on a 1994 PowerBook 280c and that the hardware and software are self-contained; together they make the piece.

Knowing that the hardware and software rely on each other to present an experience for the visitor which is faithful to the artist’s original intention was crucial in our understanding of the piece. We addressed them separately in the lab, documenting along the way.

The artist was unsurprised to learn that, even after 20+ years, the PowerBook 280c powered up as expected the first time we turned it on. Simon wrote a custom program in the C language for Mac OS8 which is mounted directly onto the PowerBook and launches on startup. Mr Simon, Jr. retains the source code and only the binary code can be obtained from what he provides upon

acquisition (the floppy disk, above).

Treating works like Color Panel v1.0 often requires trade-offs or accepting certain limitations in order to bring a work ”to life.” While we did find a single dead pixel on the original display (see image, right), the software component of the work was in excellent condition, so we chose to focus on the hardware.

When the 1994 Mac PowerBook 280c is powered on, a custom program written by the artist launches automatically.

A “dead” pixel in the display.

Software

In time-based media artworks, it’s important to define which properties of the piece make up its core identity and which aspects are variable. In several interviews that I was able to find the artist has stated that the code and the hardware are not variable and should be maintained as well as possible. In fact, he said that the piece should only be displayed on a 1994 PowerBook 280c and that the hardware and software are self-contained; together they make the piece.

Simon wrote the program in the C language for Mac OS8. It’s mounted directly onto the PowerBook and launches on startup. Mr Simon, Jr. retains the source code and only the binary code can be obtained from what he provides upon acquisition (the floppy disk, left). At The Brooklyn Museum, we chose to focus on the hardware and let the software exist in its current state, since this was a summer project and we had limited resources to perform this type of advanced digital forensics into the computer’s hard drive.

A green LED lit up on the inverter board the first time we turned the work on.

Above: Cleaning the work’s acrylic housing

Right: A view of the back of the sculpture, showing the dissected 1994 computer.

Hardware

Conservation Documentation

Click on either of the images above to view

reports made for this project.

Reports

It is often the case that the bulk of efforts in time-based media conservation are spent on documenting the various relationships, dependencies, and technical aspects of the work in question.

In my time at The Brooklyn Museum, I created two reports. The first is a condition report which describes the work’s current state and was produced using The Museum System (TMS). The second is based on templates used by institutions like The Tate and The Museum of Modern Art. This report is more comprehensive and includes product manuals, exhibition history, interview transcripts, and other important information.

“…Since these laptop components won’t last forever, the first thing you’d want to do is exhaust all supplies of 280c’s...But at some point, we’re not going to be able to get them. Then you must decide whether you go to, say, a 14-inch LCD panel, or whether you’re going to allow someone who owns the sculpture to refabricate the display.” -John F. Simon, Jr.

Artist Interview

Mr. Simon, Jr. was kind enough to sit down for an interview with myself and my supervisor at the Museum, head conservator of objects Lisa Bruno. We gained important insight into his working methods and his feelings toward replicating the tangible and intangible aspects of the work:

“…The piece should only be displayed on the original hardware - the piece is self-contained - hardware and software together make the piece...The whole piece should be preserved by replacing hardware parts.” -John F. Simon, Jr.

My experience thus far has made interviewing artists, both formally and informally, one of the most enjoyable parts of contemporary art conservation. It’s often possible to gain unexpected valuable insights into their process or philosophical approach. In this case, museum staff had never questioned the future of the work, and hearing Mr. Simon, Jr.’s point of view, that hardware and software are intrinsically linked and must be maintained, provided a guidepost for its preservation.

Future of the Artwork

My work at The Brooklyn Museum required creative problem-solving to understand the condition of a computer-based artwork and helped the museum gain institutional knowledge about an important piece in their collection.

Ultimately, while both hardware and software pose their own unique conservation challenges, the issue of diminishing stocks of Apple PowerBook 280c’s mean that the piece, one day, may need to be fitted with an alternate display (one which may not even exist yet), or need to be retired or deaccessioned. Understanding treatment options for artworks with hardware dependencies is an important part of time-based media conservation, even if that means the work is unable to be activated as intended and therefore unable to be exhibited.

I remain incredibly grateful to The Brooklyn Museum for providing me with an internship which was so fulfilling on both a professional and personal level.

I am particularly indebted to the staff

at the Museum, including:

Acknowledgements

Lisa Bruno

Carol Lee Shen Chief Conservator

Bob Nardi

Director of A/V and Time-Based Media Conservation

Tina March

Associate Conservator of Objects

Victoria Schussler

Assistant Conservator

Natalya Swanson

Conservation Fellow

John F. Simon, Jr.

Artist

I am also grateful to my professors and advisors at The Institute of Fine Arts, NYU, including:

Michele Marincola

Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor of Conservation and Chair of the Conservation Center

Christine Frohnert

Research Scholar and Program Coordinator of the Time-based Media Art Conservation Program;

Co-Founder and Conservator, Bek & Frohnert LLC

Dr. Hannelore Roemich

Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Conservation and Chair of the Time-based Media Art Conservation Program (Retired)